Art's Trojan Horse

A weekly podcast on Art and Life

Art's Trojan Horse

The Factory: autobiography 5, 1974-5

From skimming the pit in the meat factory to riding the Lansing Bagnall across the factory floor, while trying to hang on to a dream.

THE FACTORY

Throughout the 1970s I worked in six factories and for twelve other establishments when not in education or between jobs – on the dole. From picking strawberries and peas to shovelling pig slurry, I hated working on farms.

Back at school, the maths teacher Mr Whitely, would clap his hands sending up a cloud of chalk and exclaim that the failures among us would be destined to work at the local meat factory as if a prison sentence.

Whitely was correct. For a few weeks IN 1974 I ended up in the old pork hall, where pigs were turned into all manner of products – from sausages and bacon to brawn and lard. Employed as a temporary cleaner, I got to see all over the factory from the abattoir to the bacon lines to the lard plant; from the fat-gathering basement to the void.

The factory had such a powerful influence on me through its bloody imagery and the workers struggles to retain their humanity in such a demeaning setting. I had regular cleaning jobs. One was to “skim the pit” in the basement (skim the pit of its maggot-ridden fat) and the other was to clear the evidence of what was then called “courting couples” who snuck up to the void at the top of the plant to express their affections.

So, in response I wrote a series of poems about an imaginary young woman working at the factory. Here is a snippet:-

Pig pieces zipped into plastic under vacuum,

Flies Vaponarized. Ladle skims a pit of fat.

Here is lipstick. Baby doll, vermillion, a protein kiss.

She adjusts a blade. Pig pieces fall. She hears

A man call: “Move it – ain’t a dog’s dick!”

Kidneys skid across dishes, Brut in her ears,

She hears some sexist shit.

Blubber cold sow part, ribbon guts on fingers

Pulled from black plastic. Grinning pig faces

In stainless steel basins, pig faeces on floor.

Trees of meat passed between plants

Past hedgerows of jellied skins. Sex

Is a game of a butcher’s knife away.

Abscess halts incision and they have it away

Life’s caffeine up in the sweaty hot, hot void.

Hopper full of pepper ground,

A grate of two cogs out of tune,

White noise, a cage, armies of hands on the pig.

After four weeks, I left. A friend told me it was easy to get a job – remembering this was May 1974. Just go round and ask for a job.

The first factory I called at was a warehouse. Hille International then had a manufacturing plant nearer the town and this warehouse of goods on the estate. Only part of the plant was devoted to manufacture and “product development,” the rest was for warehousing. They made furniture and were mostly famed for stadium seating, alongside high end chrome and leather armchairs.

I got a job directly – the next day! I was employed initially as labourer and gofer. There were around a dozen working at the site and three managers. For the first few days, I just did what I was told, helping load and unload lorries. Within a week or two, I was driving around the warehouse on the Lansing Bagnall, moving stillages and pallets of goods from one place to another.

Quickly I was promoted due to failing eyesight – no, not my eyesight but the manager responsible for goods in and out. He couldn’t read the serial numbers or dispatch papers, so I took on this role.

Though it could be quite boring work, it was never mind-numbingly terrible. The come and go of lorries and other jobs assigned to me, meant the days past. It was May 1974, Harold Wilson was running a minority government with Heath’s three day week and the NUM miners’ strike behind us. I soon became a member of the Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU) and was gobsmacked as three of the dozen employed in the warehouse were proudly non-union. Ah, the rural dwelling folk!

Within a few months, there were strikes and I knew instinctively which side I was on. Pay and conditions were relatively good and you get neither by saying “please.” However, later in the year, redundancies were announced, in negotiation with the union. Though I was last in, my name wasn’t on the list. However, the three non-union workers now faced redundancy. One of the three was an elderly tea boy who had learning difficulties and all the workers at the warehouse disagreed with both the management and union – he had to stay! To that end, we were successful.

When right wingers go on about Health & Safety as a burden of red tape, it’s not their lives helped by such regulations. At some point, management decided that polypropylene furniture could be burnt in the yard. Even now, research is hazy because different mixes of chemicals can be far more toxic than others. Anyway, I was asked to burn such chairs. Immediately, on ignition, I knew the chairs I was burning were dangerous – as I heaved and coughed.

After talks between the leading technician, union rep and management, the head of the fire service paid a visit and stipulated that one chair could be burnt at a time. In other words, he was backing management. A few weeks later, it was noted that kitchen and living room flat pack furniture had been sent to the fire officer’s private address…

Luckily for me, the leading technician burnt the chairs from then on.

Workers at the warehouse felt quite confident as 1974 turned into 1975. At Christmas, we all lined up to get our company turkey and bottle of wine. My parents were thrilled to bits with this!

It was suggested that I should become a shop steward but because I was single I declined. I would have called for a strike at any and every opportunity – and if there are small mouths to feed, well, better a family man or woman for the post, I thought. However, I was really encouraged by their faith in me and I felt like a real worker.

However, come lunch breaks, there I was with a book up the corner. I had my dreams still. And one of those dreams was taking shape.

Back in the late 1940s my parents had produced art catalogues on a small Adana letterpress machine. Their type face was Gill Sans I recall and they had 10pt, 12pt, 14pt and 18pt fonts properly laid out in trays in a wooden cabinet. Anyway, the machine was idle so my dad gave it to me. I began to learn type-setting with a view to printing my own book of poetry.

Type-setting is incredibly time consuming but I made a start. There were trips up to London to buy a new type font, spacing material (leads), ink and new rollers for my 6 by 4 inch Adana Press. I could now set a block of type, lock it into place in the chase with quoins and take a proof.

I left Hille International a year into the job and with money saved from work, I bought a second-hand Roneo duplicator and a long arm typewriter, together with more Adana printing equipment. So, in the spring of 1975 my little press was set up.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

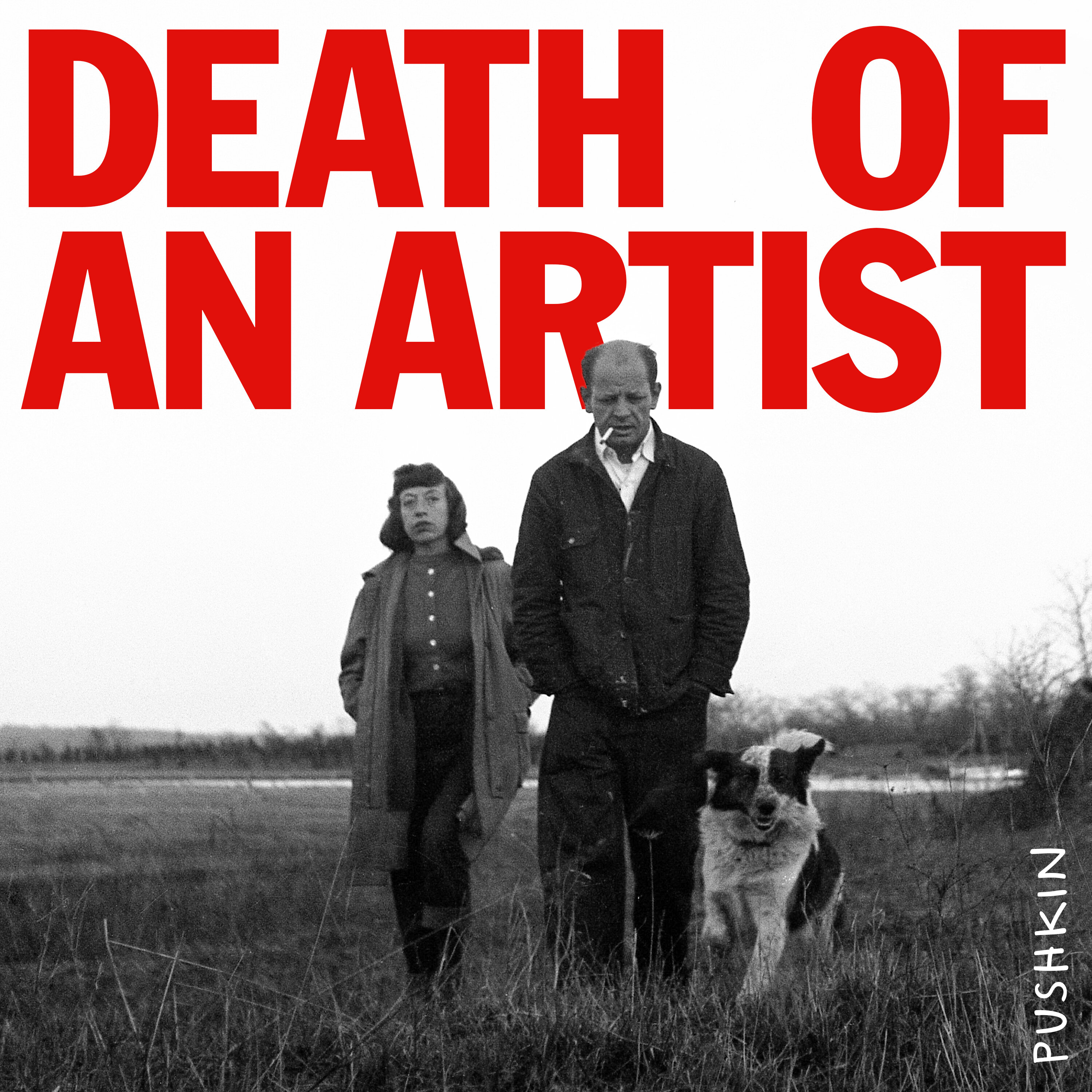

Death of an Artist

Pushkin Industries

The Week in Art

The Art Newspaper