Art's Trojan Horse

A weekly podcast on Art and Life

Art's Trojan Horse

The Death of Community Arts

This first of seven talks on the arts looks at the rise and demise of Community Arts,

THE DEATH OF COMMUNITY ARTS

From the outset, I must say that today’s art for health and wellbeing should be praised and applauded. Art based projects assisting those suffering mental and physical illness can be essential, while art activities outside school are not only enjoyable for children, these can provide a nourishing and stimulating input away from the cold cage of the national curriculum and the point scoring of Ofsted.

However, where did art for wellbeing come from? The simple answer is from community arts which proceeded wellbeing arts. Yet, do we know where community arts originated and can its history, decline and death tell us anything about present and future practice of arts in the community?

I speak with no academic authority, though I have over 25 years experience of working in what was then termed community arts. More than this, for my BA I majored in fine art (sculpture), alongside studies in the history of art and contemporary drama; my MA was in contemporary theatre; and for a PGCE I studied Drama and Media Studies to teach in the FE sector.

I ran hundreds of workshops, courses and projects in state schools, sixth form colleges, Education Otherwise, in prison, in YOI’s, for an array of charities, for the museum service, the WEA, adult education, the youth service, youth theatre groups and many, many more. I crossed over between the visual arts, creative writing and drama. Projects delivered included a youth theatre history play, two rock schools and a graffiti night at a youth centre – heavily criticised by the local press!

I also taught those with learning difficulties for eight years, often through arts projects. And for a lifetime I’ve tried to balance teaching with community arts work and producing my own work.

Often, in creating my own work, I helped to found small communities of like-minded people, so I was quite central to a number of groups (Haverhill Poetry Group, Ipswich Poetry Workshop, Ipswich Community Arts Group, InPrint, Creative Working Lives and more). Indeed, in churning out poetry (an often isolated activity), I subsequently had 400 poems published in the large network of printed magazines which flourished in the 1970s and 80s. The sudden growth of these little magazines mirror the development of community arts, in some ways.

Community arts origins lie in the social upheavals of 1968. While there were artists involved in working class communities before 1968 – such as agit-prop theatre and elements of the folk music scene – the civil rights movement in the US, the Vietnam War and all the constraints and attacks on the working class in an age of consumerism – sparked the “fire” for social change – a fire which lasted nearly a decade across the globe. In Britain, women fought for equal pay, legalised free abortions and more, while there were also movements to claim squatter rights and in reclaiming the streets. And in workplaces, there were waves of successful strikes and occupations against low pay and poor working conditions.

From this cauldron demanding change, community arts emerged, alongside the rise of political theatre and a questioning of high culture.

Theatre was central to community arts, though there were specialisms such as mural painting.

There was a notion that community arts could not only promote and highlight a campaign or an injustice, but could provide the tools for an egalitarian arts provision, bringing people together.

As community arts developed, there were concerns:

1. Who would fund community arts?

2. Could this DIY art forms ever create binding objectives for

community arts?

3. Was there an aesthetic or literary worth in community arts?

4. What is art and what is just an interest?

By 1978, as Owen Kelly puts it in his book ‘Community, Art and The State’, community arts had shaken off the age of Aquarius and faced up to some hard questions. The Association of Community Artists (ACA) had to decide between TUC affiliation and possible union funding or enable ACA to oversee funding from the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB). Already, the ACGB was making funding cuts, even though a lot of funding was devolved to some 12 regional arts associations. Had the ACA determined that these artists would not rely on state funding, I doubt community arts would have survived for so long. Yet its socialistic character may have enabled the ACA to galvanise some basic objectives.

Another concern, signalled from on high, was that community arts would diminish the quality of art. This has always been the stick to beat amateurs and working class artists with. There were ways however to make community arts the most vibrant sector:

· regular regional meetings

· training residencies

· skills sharing events

To some extent, regional meetings, training residencies and skills sharing events took off in the 1980s and early 90s. Eastern Arts ran group meetings into the 1990s. Here they hosted residencies and skills training events. And while I was in Leicester in the mid-80s there were high profile residencies introducing participants to an array of new skills.

However, cut followed cut and all this was swept away. The tail end of community arts lingered into the Tony Blair years and there fizzled out. Sure, the state still wanted “community” acknowledged in art council applications, but “sustainability” and “joined up thinking” were just the mirage of a government beginning to sell off the NHS via the Public Funding Initiative.

Then the 2008 crash. Cuts upon more cuts. “Community” was no longer a buzz word and the arts were tightly in the grip of the state’s arbiters once more.

Cuts weren’t just made to arts budgets of course.

When you take away so many mental health specialists and facilities, what is there left to alleviate the suffering of the dispossessed but Art? I see that need – totally.

It is both Tory and Labour governments which have perpetrated the deep erosion of the Welfare State, including the NHS, which has created a lingering void in society, particularly within the working class.

Looking back, there were some amazing companies like The Welfare State International, Red Ladder and Inter-Action. The Islington Bus Company provided cheap or free printing to community groups, while the Directory for Social Change compiled an alternative network of organisations bringing the needs of people together, and Another Standard magazine provided articles on best practice in the field. They published their own manifesto in 1986.

But all too late. The defeat of the miners in 1985 was pivotal in arresting this branch of the arts – as youth services were shut down and clubs closed; as mental health resources were cut to the bone; as community hubs and projects were terminated; and as the NHS began to flounder, social care crumbled.

Rather than a new configuration in the arts, Arts and Wellbeing owes much to community arts – its achievements, not just its demise.

Yet, probably under another banner, community arts will rise again, not for any sentimental reason but because there will be another fire soon.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

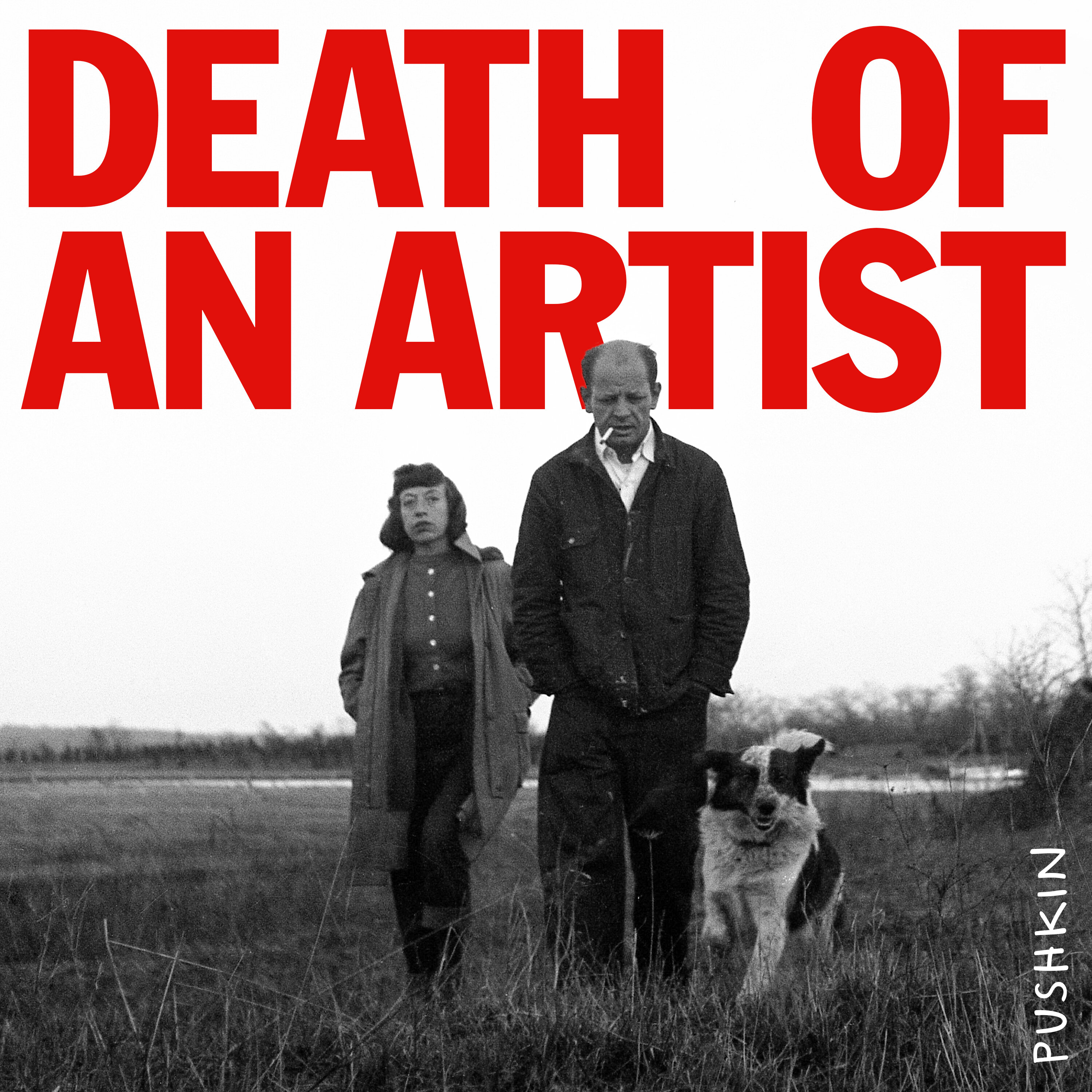

Death of an Artist

Pushkin Industries

The Week in Art

The Art Newspaper