Art's Trojan Horse

A weekly podcast on Art and Life

Art's Trojan Horse

Riotous Exhibitions?

A search for a riotous exhibition or its spirit took me to Gustave Courbet in the 19th Century and a little publicised show of kinetic art in Amsterdam in 1961.

RIOTOUS EXHIBITIONS?

I had been looking back at the history of gallery exhibitions to see how many riotous showings there have been, or at least, exhibitions which break from long established norms of looking at pictures and walking around sculptures. Of course, the history of art is littered with rebellious artists; and there are genres of art which have lent themselves to the rebel spirit – caricature, cartoons, photomontage, for example.

One of the great rebellious artists did over-turn the establishment, to some extent. Gustave Courbet (1819 to 1877) circumvented the Salon structure in Paris, which was based on patronage, where artists were invited to exhibit. One year, several of his huge paintings were rejected, so, in response Courbet set up a makeshift gallery next to the Salon! A dissident anarchist-cum-socialist, Courbet assaulted and changed the very subjects of painting itself. Stone Breakers 1849 chose workers in poverty as the subject of his large painting. Unlike Millet’s romanticised depiction of peasants, Courbet’s realism turned art towards the masses.

Not only did Courbet push realist subject matter, he began to challenge perspective, where his figure (often himself) seems to be breaking free of the picture frame. Realism was born, the first major “ism” pointing towards Modernist Art in the following century.

Had it not been for the short lived Paris Commune (1870) Courbet may have settled back into some kind of conformity. Though Courbet’s socialism was, to some extent, self-styled, he embraced the Commune. He set up the Federation of Artists, which stood the old Salon on its head, where the artists themselves controlled, through democratic accountability, the galleries.

As the Commune was quashed (many died, many were imprisoned), Courbet got off with a six month prison sentence, after which he exiled himself to Switzerland, descending into drink. However, his attempts at democratizing the arts re-emerged in the early years of the Russian Revolution.

The avant garde were enthused by Courbet’s radicalism and attacks on the establishment, though he also wanted to be lauded by that establishment. Thus he epitomizes the contradiction of the Modern artist: originality and standing up for one’s beliefs versus paying the bills.

Modernism was very much the Twentieth Century. The artists and poets of Dada and Surrealism were indeed rebellious but the galleries and the systems of patronage continued, to a great extent. Yes, following the huge upheavals of war and revolution, the state – in the USA, Europe and UK in particular – played a huge role in developing galleries and art centres. But look at our largest and greatest institutions today and they’re swimming in business sponsorship. Giant companies back the recently developed system of gatekeepers and curators in cahoots with the state.

However, to a limited extent, artists have some power, depending on their status. They can withdraw their work or join gallery sit ins and the like (most recently actions taken against companies supporting Israel’s genocide in Gaza, for example).

One artist who is a hero of mine is Nan Goldin, who is an effective campaigner. I’ll talk about in another podcast.

It is true artists have challenged assumptions about art – from Andy Warhol to Tracey Emin. Back in the 1960s Diter Roth filled suitcases full of cheese and let them mature in a gallery space (‘Decomposition’ was the title of his exhibition); and in the 1970s Stuart Brisley sat in a bath of offal in a London Gallery, while Carl Andre’s bricks sent the Sun and Mirror apoplectic.

From a nuclear submarine, made of rubber tyres, set on fire by an irate visitor, to a lifetime’s collection of objects shredded to dust, artists have pushed individual boundaries but do artists only act in pursuit of their own aesthetic and financial goals?

In 1970 a group of New York artists supported calls for a ‘US emergency cultural government’ in response to the Vietnam War and the immediate situation where state troopers had shot dead students opposed to the war. This led to leading artists – Lichtenstein, Dine, Stella, Oldenburg and others – to boycott the Venice Biennale, “a US government sponsored” art show. The artists won and the US withdrew from the event.

However, this doesn’t answer my quest for a riotous exhibition. The “International Exhibition of Art in Motion” in 1961 comes close. Over 450 guests enjoyed an opening dinner and Thelonious Monk provided the music. The exhibition itself was pulled together via a number of European and US art directors, who relied heavily on the artists themselves to bring the event together.

But, said one critic… “The exhibition is sensational and has provoked astonishment, chagrin, and some violent outcries.”

The vice squad was called and charges were brought against the director as “an obscene instrument was removed from the exhibition.” The work in question, by Robert Mueller was ‘The Widow of the Bicyclist.’ Incredibly, from old bicycle parts, he had created something crude and obscene. Imagine the hilarity of the ordinary people attending the show!

The exhibition was panned and vilified. Some exhibits moved too much, some didn’t move at all and there were – dread the day – ‘happenings.’ Critics loathed the exhibition. The hierarchy of kinetic artists had been brought down. Exhibits included drawings and plans of things that might be built! There was fear on high! And how can artists moving about in a space be considered art? Most of their ire was vented on Jean Tinguely – a key artist involved in putting the exhibition together. Among other things, they charged him with being a neo-Dadaist! Of being an anti-artist!

However, the huge crowds loved the exhibition! Art that moved, art that visitors could touch! Buttons to press! Thousands attended. It was a very successful exhibition and the art established detested this as much as the exhibition itself.

A year or two later, Jean Tinguely created a moving sculpture for the New York Museum of Modern Art. He invited guests to take the thing to pieces. They obliged, taking away small parts as souvenirs, perhaps pondering trips to the auctioneers. However, the directorate intervened and firemen were called to assert health and safety guidance. The offending art work was taken out of the gallery.

So, we’ve got quite close to a riotous exhibition. Would that we could have a little of that spirit back today?

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

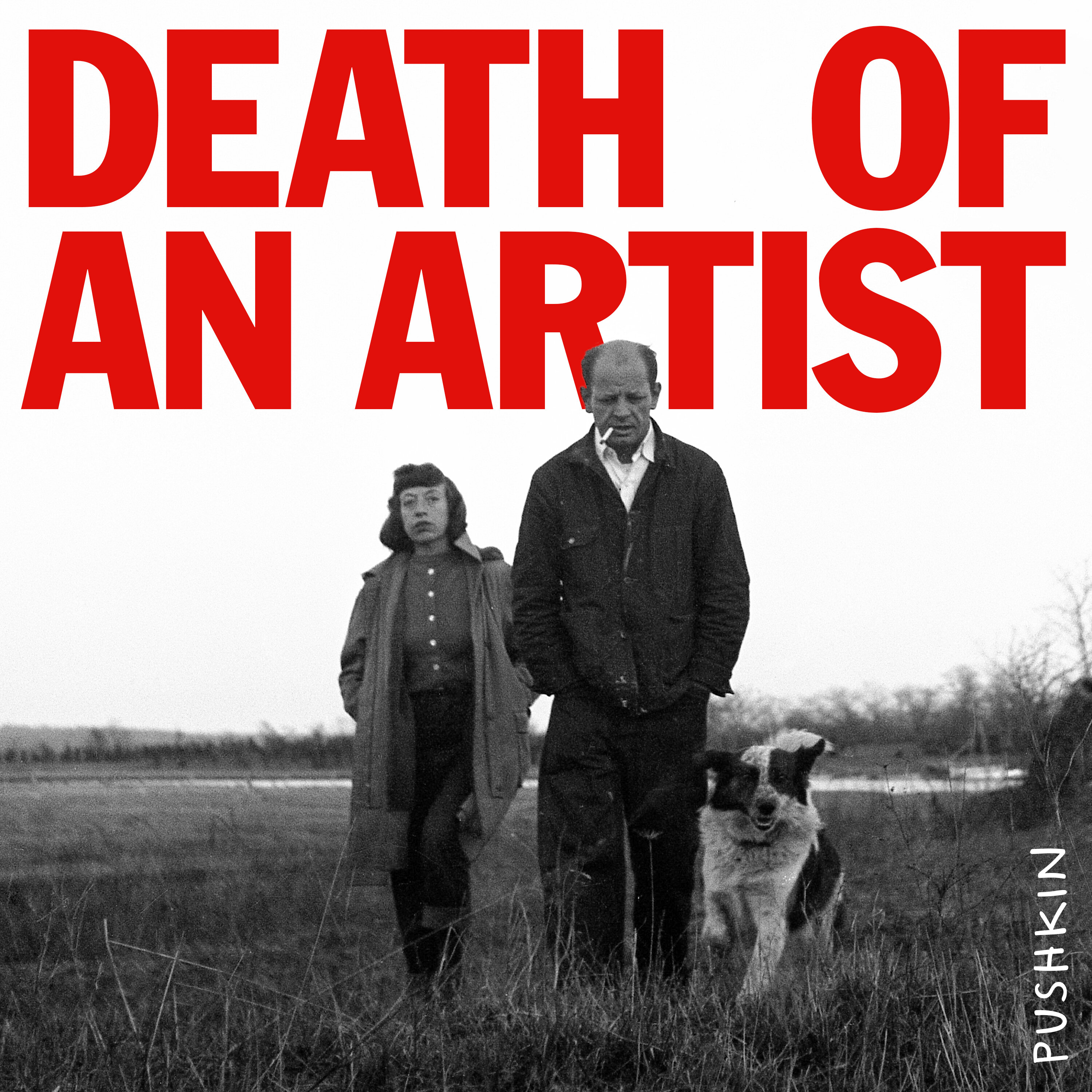

Death of an Artist

Pushkin Industries

The Week in Art

The Art Newspaper