Art's Trojan Horse

A weekly podcast on Art and Life

Art's Trojan Horse

From Art School to AI

We're going weekly! Every Tuesday evening at 8pm there will be a new podcast on Art and Life.

In this first Tuesday edition: Against AI in Art, The Black Box Experimental Theatre 1965-71 and the first of several art school recollections.

AGAINST AI IN ART

A young man entered my studio, part of an open studios event. He said he wasn’t into “all this” traditional art (painting). He runs a ‘hacking space.’ So I asked him to sell me AI in Art. He was full of enthusiasm.

“Say, you want to ‘paint’ a tree.”

“Ok. I have painted trees.”

“There are virtually millions of paintings of trees on the internet. Here is your resource – your palette. AI, in response to what you want, filters through those trees until it finds a configuration, a combination of trees from which you can morph your tree ”

I thought a moment.

“I can see that your AI tree or trees reconfigured, morphed, whatever, could be unique but will it ever be original?”

“What art is?” the young man rallied back.

I thought for another moment.

“Even if it is unique – and original – where is the expression? We express emotions through art, where is this expression?”

“The expression is already there – in that soup of images. It is human, it is historic, it is collective…”

If I smoked, this is when I would have lit up.

I tried to drill down into his statement: “Isn’t yours a perfect post-modern view of art. You take the painted trees out of their contexts and create a new context for them, without reference to their history.

“Didn’t Surrealism do that?” he cut in.

“That’s a tough call…” I stalled for time to think: “A photomontage of a machine gun in a pram is given a new, powerful context; it creates a new narrative which the viewer questions. We, the audience, have our senses woken: a baby’s pram hosting a vicious weapon of war. The collage asks us to consider the nature and reality of modern warfare.”

He looked back at me befuddled: “I’m just talking trees,” he said.

We parted on cordial terms. “There’s much to work on,” he said with a grin as he parted.

We all take shortcuts. Few sit in darkrooms to expose photographs these days. That is, photography has a short cut in its digital form. However, I still prefer to use my SLR camera than my phone, though there’s more control on my phone and it’s easier to access. Yet, it’s all in the image, I think.

The availability of old tech diminishes and, in many cases, is now unavailable.

Way back in 1973 or so I hand-set a book of poetry using 10pt letterpress. This took many, many weeks and was good therapy as I couldn’t concentrate at all in early adulthood. Of course, I always looked for a shortcut and eventually found a Roneo electric duplicator. Words were typed on a skin, creating a mini stencil of each letter through which the ink would pass as its big roller fleetingly flew over the paper. With care, one could also draw on the skins. For me, this wasn’t my Bob Dylan “Judas” moment. It was a faster printing method.

Then photocopiers arrived. Again, this was an advance and many of us have printers attached to our PCs and phones these days. Yet, I yearn for the aesthetic roughness of that old duplicator.

However, the anarchy of capitalism creates confusion: technology’s enemy is time. Each invention has to be superseded and the old technology dumped. Technology doesn’t want you to find your own shortcuts in life and art.

Back in the late 1980s I attended a wonderful weekend training event for community artists at Loughborough University. Two artists used old slide projectors to create an incredible installation/performance using slides created by all those attending the event. The colour and movement was incredible and I’ve not seen an immersive show since to cap that powerful, low tech projection.

I am not arguing against digital. However, I am against that ‘Bluey posing as art’ syndrome and why make art third hand when we’ve the mush of Jeff Coons?’ Without getting your hands dirty,, ‘new and shiny’ can be utterly miserable.

At a recent graduate show of art at NUA, out of scores of works, two stood out: one was a series of highly personal and emotionally powerful etchings and the other was a giant painted landscape triptych. The woman who painted the semi-abstract landscapes made the ground soar up into the sky in a way I’ve not seen before. Traditional methods do not mean old fashioned art. Here was the vibrancy of what should be viewed as a New Modernism in a world even more frightening today than in 1925.

Art is not about trees but what is happening to them, and to us.

Influences on my work. I include this recollection because it cuts across the grain of my beliefs and presumptions.

THE BLACK BOX: An experiment in Visual Theatre, 1965 to 1971

Poetry is not created free from the World nor from other poets, the living

and the dead, which applies to the practice of all the arts. An influence I have tucked

away for some years was and remains ‘The Black Box – An Experiment in Visual

Theatre’, which was a six year experiment in the 1960s retold in a book about the

project published by Latimer New Dimensions (Number 2).

This project was a collaboration between artists and art students at Exeter School of

Art begun in 1965. Ultimately it was led by John Epstein and a small, dedicated

group.

It was born out of a desire to animate the surface of paintings; to enable paintings to

be part of a contextualized live event. As a piece of theatre, they required a story

and found it in Piktor’s Metamorphosis by Herman Hesse. This mystical fairy tale

was the catalyst for their production and its framework. They called their production

Changes.

Paintings triggered by the story were the group’s collective starting point but their

visual experiment was to be the combination of two and three dimensions. Slowly the

Black Box developed into a 24 by 20 foot box structure, with just one wall open.

Within the box there were ever changing images, laid over other images and objects

– and actors – creating the illusion of space during the journey of metamorphosis – a

man turned into an aging tree; birds, butterflies and beasts turned into each other.

These effects were achieved through the use of Pepper’s Ghost, projectors, moving

objects and, most importantly, cine film. One of the projectors was wheeled into the

space on rails!

The team battled with the technology, finding space to build the box and the money

to keep the project and themselves afloat.

Of course, today, such an adventure would occur in the digital space of immersive

theatre via headsets and visors. The Black Box of the 1960s worked precisely

because it was an interface between the physicality of experience and the illusion of

film and other optical tricks.

Prior to all things digital, there were experiments like growing mould on 35mm

celluloid film, for example. And there were projects in the Seventies and Eighties

which pushed projected images to their limits - and tested photocopiers to breaking

point to create original effects (such as photocopy films). Very quickly, real space

has given way to digital space and the attributes of accidents associated with

physical experimentation have been reduced to the certainties of pixels, where even

the mathematic shapes of fractals pose as art.

We seem to have lost the real life friction of physical objects.

The Black Box group eventually moved to London and found space to house their

experiment. Of performances recorded is the last at The Roundhouse at the end of 1970.

Of course, I didn’t get to see the Black Box or a production of Changes. However,

Ken Smith was poet in residence at Exeter Art School at the time and gave his

thoughts on the venture to the group. He described the treatment of this allegorical fairy tale as being somewhat “flat.”

It is important to note that the project was not the performance of a play. Indeed, the collaborators tried to get away from labels, such as multi media. Changes

certainly was a visual experiment of note. Today we’d call the Black Box an art

installation.

Perhaps the Black Box team fell into the trap of illustrating a story? Today, as then,

many present story telling as theatre, as a play, yet a play has its own dynamic:

show not tell is one of those golden rules, for the troupe tells rather than shows here and the work becomes a tale. Stories tend to be linear in their unfolding. Unless one finds some circular, diffracted or back-to-front structure, this will be recognisable as a story. In Changes part of the problem seems to be that the artists strived for a unison and harmony with the natural world whereby “change” invokes no friction or conflict – metamorphosis rather than a conflict which changes the subject.

Indeed, from musician to producer, each wanted back to the rural idyll, through

nostalgia rather than history. They wanted to create a unison and harmony

seemingly at odds with the times they were living through.

Nevertheless, this was an heroic experiment in the visual arts – an incredible art

installation. I wonder what happened to the materials, images and objects of their

brave experiment?

My art school adventures.

It was 1982. I was studying art at Middlesex Polytechnic and I was on a placement at the main art school block, Quick Silver Place for several weeks. On this occasion I was sitting in on a “crit” – a critique of second year BA art students’ work. This was conducted by an esteemed artist and tutor. We followed her around the gallery from one piece of work to another. Then we arrived at Kevin’s offering.

I must point out that most of the work here was sculptural and conceptual.

Kevin’s piece was of a horse lying on the floor. It was roughly shaped from shredded paper. Beneath the horse’s belly on the concrete floor was written in chalk ‘Trojan Horse.’ We clustered around Kevin, the tutor and his horse. A long studious pause became stretched silence before the tutor spoke:

“Why chalk?”

We crumpled, hands over mouths, holding back laughter. Had the tutor not got it? Had we missed it? Or was it Kevin? Or the horse?

“Why chalk?” we asked each other all day. Why chalk? Chalk had never been so amusing.

That year, a huge figure I had made was stolen. The great big, weakly gendered, lumpy figure stood in the entrance to the art block in Trent Park. With a steel armature and a solid plaster body, it was heavy indeed.

My tutor Max was quite upset at the theft, while I had grown to dislike my huge discharge. Indeed, I said: “if they want it so badly, let them keep it.”

Naively, the couple who stole The Lump were students at the poly, in our department, and had placed the cumbersome thing in their tiny front garden – a garden Max passed by in his car every day.

The figure was returned and the couple apologised. But as I said at the time, “Whose sculpture is it now?” It’s limbs were cracked, there were chips everywhere and grass had stained much of it an acidic green. So, was it now more theirs than mine? Was it?

Within months, The Lump was in the skip.

In that same fateful year, I was transferred to NE London Poly School of Art (sculpture department) as part of some sort of academic manoeuvre. Very quickly, I realised it was a macho haven for the brown ale and roll ups brigade. They even dressed like steeplejacks and soon they lived up to their appearance. A local East End vicar wanted two trees removed from his graveyard and, now, here they were, slap-bang in the middle of the studio! The macho men set about them with axes and rip saws and the cascading branches and leaves pushed the rest of us into the corners of our shared studio. And with each blow the mantra of the decade echoed: “Truth to materials! Truth to materials!”

Attitudes in the department were bad. I witnessed two females crying, one of whom left because of a kind of artistic misogyny; and a sensitive intellectual male student was so fraught with the place, he built his own lockable studio. There it stood, a big security box, only accessible with keys – a studio within a studio. Such is art.

One other young man made a habit of leaving his art diary open on his table. There it was in bold – “Rupert keeps talking about politics. What has politics to do with art?”

The Falklands War was on and after I had read this diary entry, each day I bought a copy of The Sun into the studio and wallpapered each front page to my space. Included was the infamous “Gotcha” headline.

Having been transferred to the art school as some kind of experiment, I called Max at Middlesex Poly to plead with him to take me back! Reluctantly he let me come back to finish my degree there. I left the macho men a wall of propaganda they could appreciate and never picked up that rag again.

I bumped into Kevin on my return. I asked him what became of the Trojan Horse. He said he still had it and took me to his studio space. There was a tatty cardboard box full of shredded paper and an opened packet of white chalks on top.

I looked at him and quietly asked: “Why chalk?” I was home.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

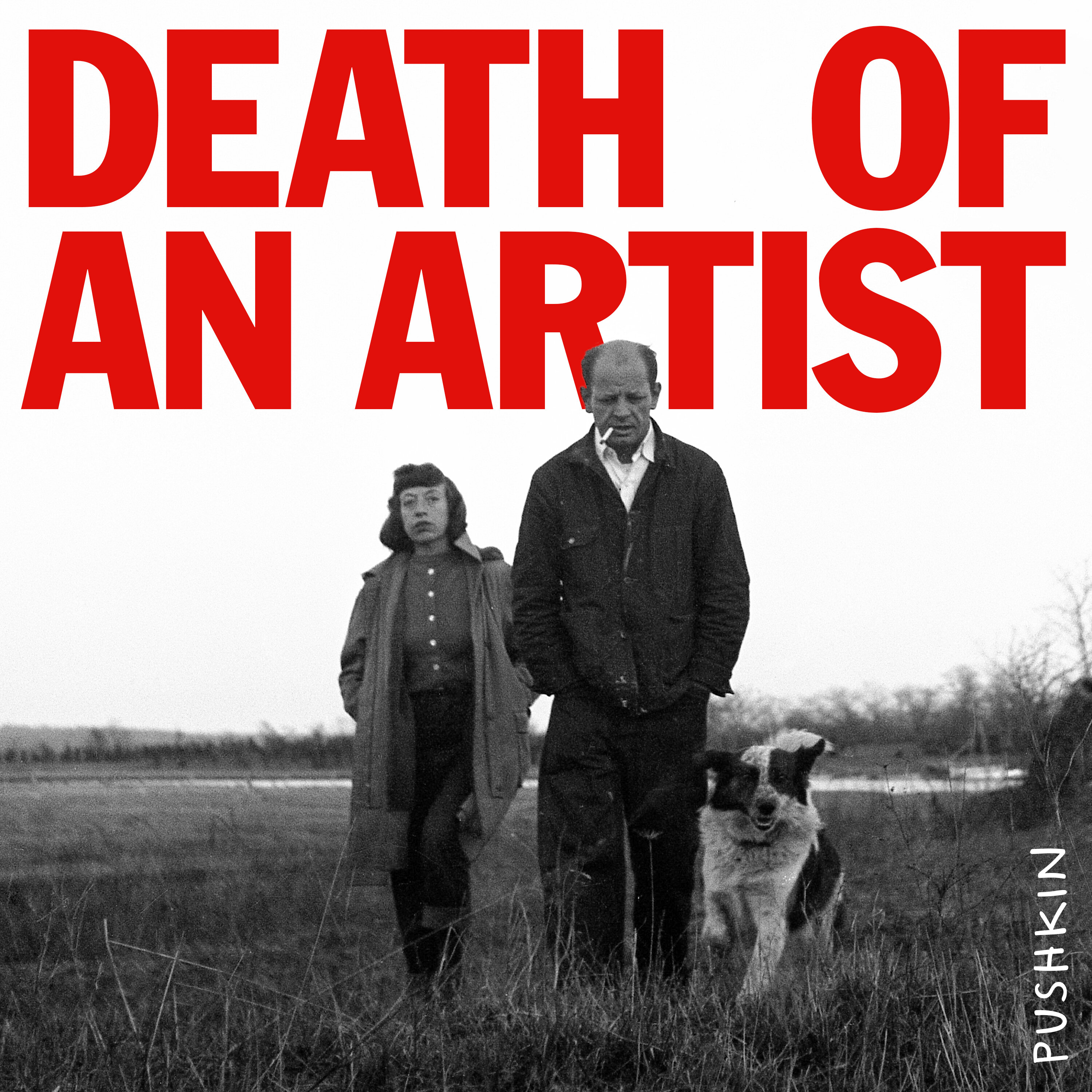

Death of an Artist

Pushkin Industries

The Week in Art

The Art Newspaper