Art's Trojan Horse

A weekly podcast on Art and Life

Art's Trojan Horse

Communism at Poslingford Corner - Rupert Mallin

I grew up near Poslingford Corner, Clare, Suffolk, close to A.L. Morton, communist historian and author of 'The People's History of England.' Here is a recollection from the time I was six, 1959.

RECOLLECTIONS OF POSLINGFORD CORNER, CLARE, SUFFOLK

I suppose I was six: the lush grass of Gifford’s Meadow unfolded from the end of our garden towards Eden, it seemed, with the Chiltern Stream at the outer edge of my world. This was a quintessential rural English scene: open, wild meadow, fat chickens roosting in an abandoned threshing machine (riddled with rot, crumbled to dust in our hands); a tumble-down scene of Suffolk pink cottages, and birdsong as rich as dreams - 1959.

To my left, Snow Hill and the village of Clare; and to my right Poslingford Corner, the humped back bridge over the stream and Ann Day’s tiny dank but inviting cottage right next to it. In front of me, the stream: a rope from a tree to swing from bank to bank; sticklebacks, sandies, bullheads and assorted tiddlers to discover hiding in the reeds or under stones of Chiltern brook; and, to the right, Orbell’s Farm and a copse beyond Gifford’s Meadow, where I once watched fox cubs play at sunset.

Most days I would be stood in the tributary or in a hole in the bank making a den. All was colour, smells, experience. Spawn turned into fat tadpoles, overflowing from jam jars and way too hot in the sun. And I could have made a temple with all the strangely shaped flints I dragged back to our overgrown garden. Yet, every few weeks the waters of Eden violently changed into a torrent of blood, bright vermilion, up to my knees, staining my legs and I would run as fast as I could back to mother.

Upstream, near Chiltern, was a slaughterhouse and every few weeks they’d wash the place down and the blood of the slaughtered was washed away into my stream. It will never leave me: that image of blood brook. They say Slaughterhouse Jack hung himself from a meat hook in the abattoir after his shift but that was long before my time.

Once, between the bloodshed events, I caught a tiny fish on a bent pin hanging from a strand of wool attached to a stick. I was sat in the storm drain of the humped back bridge on Poslingford Corner. Other kids had proper fishing rods so I was proud that day of my bent pin. As I was someway from my house, Ann Day kept a silent watch over me, over us children playing under the bridge. I’m not sure, she wasn’t as old as she looked. I believe she had TB aggravated by chain smoking roll ups. She had a big tortoiseshell cat and, when she wasn’t attending her garden, she would be reading, a vase with Chinese lanterns by her table, the cat and Home Service gently purring in the background. Ann was worldly and non-judgemental, and her tiny house was calm and inviting.

I think Ann was related to Leslie who lived in the old chapel just around the corner with his wife Vivien. Their garden was so big it had a large choice of trees to climb and hundreds of apples to scrump. Leslie and Vivien had a large summer house and a petrol mower. That was something – a petrol mower!

Leslie was tall and slim and played tennis a lot at the courts in the village and, even at a tender age, I knew he was educated: well spoken and slightly ethereal, which meant he was kind to children.

On one occasion I wandered into his garden in the summer and a group of men and a woman were talking earnestly around a large pot of tea.

My presence was not welcomed. I and Johnny Hurst retreated quickly. Later I learnt this was a gathering of Communist Party historians for Leslie was A.L. Morton, author of that seminal work ‘A People’s History of England.’ He and Eric Hobsbawm remained loyal to the Communist party, even after the USSR crushed the Hungarian Revolution in 1956.

I expect, during the early 1950s, the country’s best historians had assembled in Morton’s garden for a ‘summer school.’

My dad Tom told me that he and Leslie Morton had teamed up with Colonel Emsden in the village and went out petitioning against the British action in Suez in 1956, when I was just three.

Much later, when I was 17 or 18, I interviewed Leslie Morton as a trainee reporter on the Haverhill Echo. This was 1971 and he was still lecturing behind the Iron Curtain, particularly in Poland and East Germany then. Now, I was a pretty thick teenager and most of my questions were rooted in the damn obvious: What’s the food like? Do you feel free out there? Leslie was understanding.

A month later, I got to interview a union convenor, a rabid Stalinist, who said the problem with the Russian Revolution was all down to the intellectuals. I could see him gathering a firing squad for Leslie!

Leslie had taught at the radical A.S. Neill free school Summerhill and I expect he’s the only Communist local councillor Leiston has ever had.

For all his ideological failings, in my view, he knew which side he was on, yet, really, I suppose history itself stopped for him in 1917, sadly. However, he knew well the ins and outs of struggle in England in the years and years before.

I digress.

Life wasn’t all Communism at Poslingford Corner. Slap-bang on the apex was the Hurst Family. Harry ran a shop and, later, a wonderful bakery in Clare. Their youngest son was John who was my age, in my class at school and we played a lot together. I even went to tea at John’s and he at mine.

However, next to Ann’s cottage was the gruff Mr Doughty, a retired teacher with pebble glasses and brown cap worn severely.

Beyond Poslingford Corner, taking the right forking road, was the Barber’s Farm where I once had a ride on Topsey their pony. Beyond the farm was Hollow Ditch. I spent much time there. It was a deep cut ditch and its banks were lined with trees; and this overgrown drain was a half mile long, a labyrinthine walkway it seemed which stretched out to Poslingford. Here we kids made trails, built traps, played chase and made camps.

As we grew older, Poslingford Corner became a choice of two roads: Poslingford Village, leading to Aggie’s abandoned cottage or, taking the road left, to Chiltern and Hangman’s Hill; and at the top of hill a Roman Quarry surrounded by trees. To get there, we’d cycle past the slaughterhouse and Parker’s tiny house on wheels (yes, it was like a proper house but on wheels!) through Chiltern village. For us kids Chiltern was fascinating. There was a disused bakery, which we explored, and a run down house an old woman occupied. What fascinated us was that there was a giant hole in her front door – large enough to get a man’s head through! We hadn’t realised this was her cat hole – forerunner of a cat-flap – scored to pieces by the cat’s claws!

The quarry was where flints were once mined and it is where my brother and Brian Swann found a Roman brooch. The brooch has resided in the local museum ever since. I found nothing. Sometimes, we’d stay up the hill until sunset. Then, at dusk this deep scar surrounded by fir trees scared us stupid – and we’d pedal furiously back home.

Fast forward to 1988 I found myself writing to Leslie Morton. I had a hand in a bookshop, The Clock Bookshop, and we stocked a number of his books, published by Lawrence & Wishart. Leslie wrote back, full of enthusiasm for such a venture. Apparently, it was the last letter he ever penned. Poslingford Corner would never be the same again.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

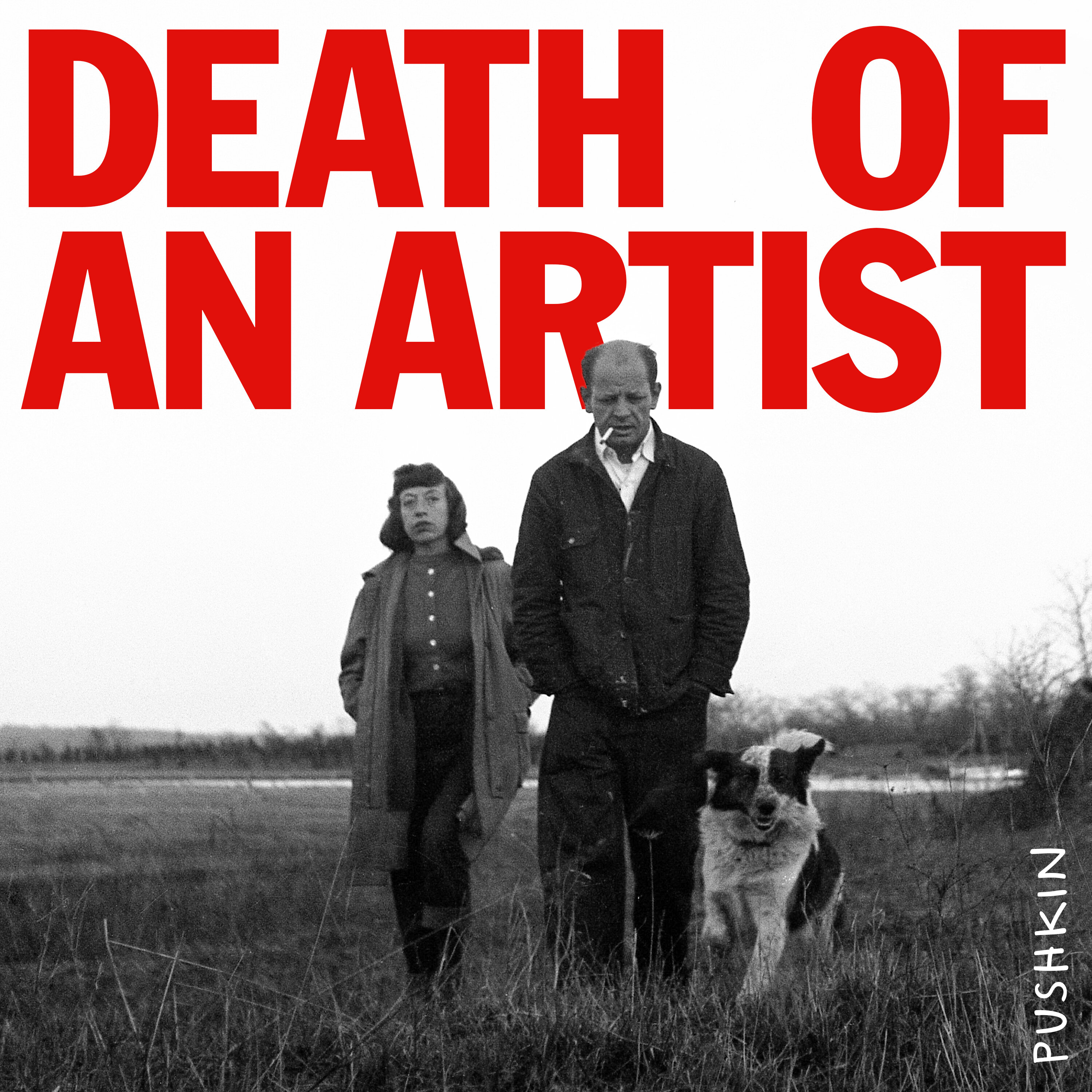

Death of an Artist

Pushkin Industries

The Week in Art

The Art Newspaper